By: Dan Urevick-Ackelsberg, Staff Attorney, and James Rathz, David Peters and Maura Douglas, Legal Interns.

Overview

An analysis of plans submitted by Pennsylvania school districts last spring, which reported how they would use new state education funding, provides vivid proof of how persistent underfunding has damaged the ability of districts to provide even the essentials of a good education. It is a window into the consequences for students of the failure to carry through on the legislature’s 2008 plan to provide schools with the resources necessary to keep pace with demanding new standards.

Although the state temporarily made meaningful strides to fix its inadequate and unfair funding, progress was reversed in 2011, when the Commonwealth cut education funding by $860 million. The impact from that cut was as foreseeable as it was widespread: Districts eliminated 27,000 jobs and class sizes increased, while test scores and the percentage of high school graduates enrolling in college immediately declined. Moreover, those cuts continue to reverberate five years later, with most districts—particularly the poorest districts—still with less state funding than before the cuts.

As part of his 2015-2016 budget plan, Governor Wolf proposed to allocate an historic increase in state funds: a $400 million expansion in basic education funding and $100 million in special education funding. In anticipation of that funding, in the spring of 2015, school districts were asked to submit Funding Impact Plans, detailing how they would spend those funds. Over 96 percent responded, with plans detailing the investment they would make in basic, fundamental resources for the benefit of their students. But as a result of a budget stalemate, additional funds were only allocated deep into the school year, and even then, totaled less than half of what the Governor proposed.

Through a Right-to-Know request, the Public Interest Law Center gained access to the Funding Impact Plans. The Plans are sobering, walking readers past the gravestones of a lost year in children’s education and demonstrating the concrete consequences of both the past year’s budget stalemate and the Commonwealth’s continual refusal to adequately fund public schools. This report is designed to equip parents, members of the public, reporters and policymakers with an understanding of just how basic those requests were, how they continue to go largely unmet, and how badly school districts still need increased funds.

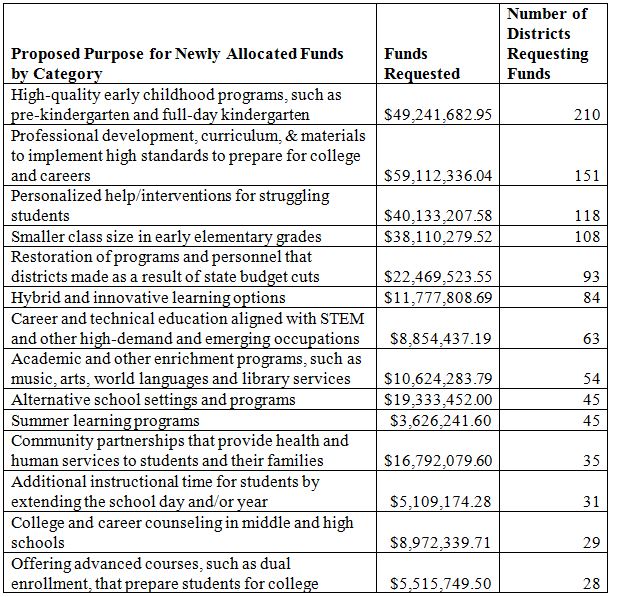

The Plans, which show once hopeful school administrators planning to devote resources to basic tenets of education, are divided into two sections. First, districts were asked to choose how they would allocate funds from among fourteen broad categories. (Districts could choose more than one category.) Districts planned spending funds on basic, integral services such as early childhood programs, books up to date with state standards, and smaller class sizes. In the second section of the plan, districts were given the option to provide a more detailed explanation for how they would use the funds. Those descriptions reveal a sobering reality: districts from every corner of the state in distress, desperate to provide students with basic educational resources.

- Download data for each school district by category of request

- Download data for each school district by narrative description

- Full Report

Proposed Spending By Category

The dire situation facing many of the districts after years of inadequate state funding was succinctly described by Riverside School District’s plan: “We would love to provide STEM opportunities and Career Readiness opportunities, but would have to use the funding to support basic necessities for our district.” The Cornell School District reiterated this reality, noting that in recent years it “has had to eliminate many programs that we feel are essential for student achievement.” The call for basic resources and the desire to provide a baseline educational program for students was repeated over and over.

Pre K and Full Day Kindergarten

The number one proposed use of new state funding was to educate the Commonwealth’s youngest students. Specifically, of the 482 districts which submitted a Plan, 210 said they would use new state funding to expand or keep from cutting vital early childhood programs, including pre-kindergarten and full-day kindergarten programs.

Districts repeatedly noted what every parent and educator well-knows: Pre-K and full day kindergarten programs are “invaluable,” “critical,” and “meet the needs of . . . at-risk students at the earliest possible point.” The New Castle Area School District for example, noted that it “operated a full day Pre-K program for seven years with the last year being 2011-12.” But “[b]ecause of funding cuts to the Accountability Block Grant and other funding sources, the District now operates a half day program.” Most districts, however, didn’t seek to add full day pre-K. Rather, they merely sought to maintain full day kindergarten, which was in jeopardy, “as expenses continue to rise and revenue decreases.”

Keeping or Restoring Teachers

Another 108 districts were going to use the money to reduce class sizes—reversing the increased sizes in elementary grades they had been forced to make; or they would use the money simply to stave off further increases. The Steelton-Highspire School District, for example, a small district outside of Harrisburg, asked for money to avoid layoffs of five elementary school teachers and keep elementary school class sizes from rising to between thirty-one and thirty-six students. That sentiment was echoed by the Dubois Area School District, a large rural/suburban district, which said the additional money “will not allow us to hire more teachers. It will simply help us to replace retiring teachers,” and thus “maintain[] current class sizes.”

Those districts were far from unique. The McKeesport Area School District, for example, noted that it has cut 110 jobs, despite a rising student population, and that it needed sufficient funding to prepare its students “to live as productive, responsible, moral, and ethical citizens.”

The Butler Area School District reiterated the same, stating it was “merely seeking to return to the previous level of services that were offered prior to the district’s budget crisis.” It detailed that it had “[e]liminated essential elementary (K-6) programs over the past two years that we aim to restore. Positions to restore include:

- 2 Language Arts Teachers

- Music Teacher

- Art Teacher

- 2 Computer Teachers

- 2 Librarians

- Physical Education Teacher

- Nurse”

And it made clear what restoring those positions would mean:

All students in grades K-6 will have additional instructional time with teachers in the following disciplines: art, music, library, physical education. All students in grades K-6 will have an increase in availability of guidance services. All students in grades K-6 will have an increase in availability of nursing services. At-risk students in grades 5-6 will have an increase in instructional time with a specific language arts intervention support curriculum.

Interventions for At Risk Students

Reflecting the need to invest in basic educational tools, 118 districts proposed reading and math specialists and other interventions to help struggling and at risk students receive personalized help and services.

- “The additional funding will be used to restore the literacy skills position for grades K to 5 that was lost in the absence of adequate funding. The position will be filled with a reading specialist whose primary focus will be the K to 3 students. . . . The development of literacy skills at an early age [is] VITAL to [the] success of a child’s education.” Ridgway Area School District.

Restoring Libraries

A large number of districts planned to restore others services critical to supporting children’s education. Ninety-three districts, for example, reported they would restore positions like librarians, music and art teachers, counselors and nurses, while fifty-four would invest their funds in new or expanded academically enriching programs in these same areas.

- “The middle school opened in 2009 and has a beautiful, spacious and functional library but has not been staffed since 2011-12. MS library science would be reinstated and the funds used for a full time librarian, reference materials and software updates.” Bentworth School District.

- “We plan on hiring a part time librarian….” Rochester Area School District.

Purchasing Books and Equipment

Many districts intended to buy needed books and equipment, including computers, in order to upgrade their curriculum and to provide teachers with the training to utilize these new tools. The reports revealed districts teaching students with books out of date with current state standards, or without equipment needed to educate students with special needs:

- “[A] new elementary reading series aligned to PA Core [English Language Arts] Standards.” Cambria Heights School District.

- “[U]pdate the math and reading curriculum textbooks and materials to align to new state standards.” Carmichaels Area School District.

- “[W]e plan to purchase a new elementary math program in order to align with PA Core Standards.” Allentown School District.

- “[P]urchase the K-4 reading series [we] piloted over the 2014-15 school year. We have not had a new reading series in about 12 years.” Ellwood City School District.

- “[M]athematic materials will be purchased for grades K-5. At the middle school level, curriculum materials will be purchased for science, mathematics, and language arts. High School materials include both mathematics and social studies curriculum purchases.” Loyalsock Township School District.

- “An Autistic Support Classroom was established several years ago in our Elementary Center. Several of the students have now transitioned to the Middle High School and the necessary sensory equipment is not available in this facility.” Burgettstown School District.

- “Restoration of elementary computer classes cut due to funding shortages. The expected outcome is students are proficient using technology including the preparation of students using programs such as Microsoft Office….” East Pennsboro Area School District.

Proposed Spending by Category – All Districts

Conclusion

Far from making extravagant requests, the Funding Impact Plans show school districts proposing to spend state funds on the very foundations of education: books up to date with state standards, and staff to provide smaller class sizes, full-day kindergarten, and re-open libraries. But students were deprived of these basic, essential services every day this year, because the state legislature and governor were unable to pass a timely budget, let alone an adequate one that would pay for even half of the programs detailed in these Plans.

The consequences of the state’s continued failures are real: Pennsylvania, according to a federal study, has the most inequitable system of education funding in the United States, with a child’s education vastly different depending solely on what side of a school district border he or she was born. Not only is that system inequitable, but it is grossly inadequate, leaving school districts of all shapes and sizes unable to provide children with the resources they need to become productive members of society.